I figured it was probably a good idea to have an outline of the Japanese alphabets here on Gakuu for easy access. There are loads of good resources out there that talk about the basics, so this post will be brief, with a sprinkling of advice on how to learn the alphabets.

So, there are four types of alphabet used in Japan.

ローマ字 Romaji – Japanese script written with latin characters.

平仮名 Hiragana – The fundamental Japanese alphabet.

片仮名 Katakana – Secondary alphabet used mainly for foreign words.

漢字 Kanji – Chinese characters and used to express major concepts.

Romaji

Well, you already know the first alphabet! Romaji is the one you’ll see used in most Japanese phrasebooks, as well as train station signs in Japan and other material that assumes the reader does not know native Japanese script, such as when citing Japanese sources in academic essays.

Words like: Sumo, Sushi, Geisha, Fuji-san are examples of Romaji in use.

There are various schools of thought about how best to deliver Romaji, the main two being the Hepburn System (used by various government agencies) and the Kunrei System (mainly used in Japanese elementary schools).

As a Japanese learner, you need not be too concerned with Romaji. In fact, I advise you avoid it like the plague, as it will only slow down your real progress in the language. That said, if you intend to do translation from Japanese, you’ll need to pick a system and use it properly. In that case, grab a copy of Japan Style Sheet – The SWET Guide. It’ll serve you well.

Hiragana ・ ひらがな

Hiragana is probably the first ‘alphabet’ you’ll learn. It’s a phonetic system that makes up the core of the Japanese language. Without it, there would no suffixes and verb inflections to tie the language together! Each character is one mora, a linguistic unit that has a fixed stress and time. In other words, each character is pronounced for the same length of time and at the same loudness. Contrast that to English, where words are divided up into syllables using various combinations of latin characters, often with unpredictable points of stress (loudness or pitch).

A couple of examples:

Gakuu (がくう) – 2 syllables (Ga-kuu), but 3 moras (Ga-ku-u).

Gakuranman (がくらんまん) – 4 syllables (Ga-ku-ran-man), but 6 moras (Ga-ku-ra-n-ma-n).

For your purposes though, you don’t need to worry about moras much until you start experimenting with different Japanese dialects and pronunciation. Just remember that some sounds are very different to English and that you’ll need to learn to speak in an overall flatter voice. Be prepared to re-learn how you move your mouth!

Also, learning to write the Hiragana script will take a little time. You can recognise it by its curvaceous, loveable appearance (ひらがな). Two weeks of practising every day should give you a good grounding. Afterwards, keep it fresh by avoiding Romaji!

Katakana ・ カタカナ

The Katakana ‘alphabet’ is phonetic and made up of moras in exactly the same way as Hiragana. The only difference is that the characters are visually harder and more angular (カタカナ). You might wonder then, what need there is for a second set of characters if the sounds are the same?

There are plenty of special uses for Katakana that make it worth your while to learn. These include foreign loan words, onomatopoeic/mimetic expressions, technical terms, for adding emphasis and use as Okurigana. You can’t avoid learning it, so start studying it early on alongside Hiragana!

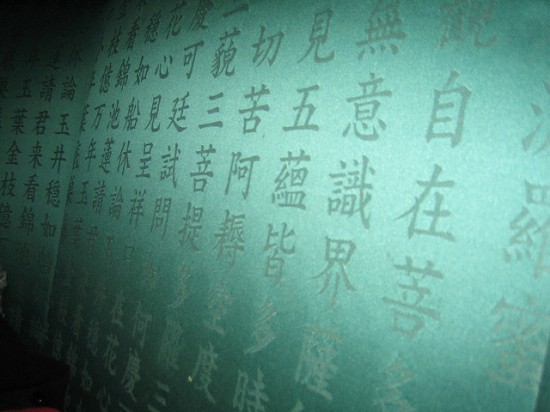

Kanji ・ 漢字

Kanji are the Chinese characters that provide the depth and meaning to the Japanese language. The standard list of Kanji (Joyo kanji) currently consists of 2,136 individual characters that you’ll need to memorise. Each comes with two types of reading: kun-yomi (the Japanese reading) and on-yomi (the Chinese reading), although there may be more than two variations in the readings for a single character. These 2000 or so symbols provide the fundamentals that you’ll need to get by in Japan, although realistically you’ll need to know a few more to be completely comfortable, or if you are reading more technical documents.

There are no tricks to learning Kanji. Constant drilling is the usual tried and tested method, although some using alternative systems like the Heisig method have reported quicker results. Learning Kanji requires exposure and repeated use in context to really imprint the characters in your mind. Unfortunately, just like most things, if you don’t use it, you’ll lose it. This is especially so for writing the characters.

Note that being able to recognise Kanji, read Kanji and write Kanji are three entirely different skills. You can get by quite well by just recognising what the Kanji characters mean (and even decipher some of the Chinese language without having ever consciously studied it!) But you’ll need to be able to read and vocalise the characters if you want to live comfortably in Japan.

Finally, learning to write the characters is mammoth task that eludes even the most fluent users of Japanese. Without regular practice penning out the strokes (and no, typing on a computer will not help), difficult characters are quickly forgotten. You can take refuge in the fact, however, that many Japanese people also find themselves forgetting how to write tricky characters. It’s probably best to first prioritise boosting your reading ability before worrying too much about writing, although the two skills are often best learnt together.

And Others…

Two related terms you may occasionally come across but are not separate alphabets themselves are:

Okurigana (送り仮名) – the suffixes following kanji stems.

These are the parts of the word that inflect verbs and adjectives, allowing you to know what tense we’re speaking in (such as past, present or future) as well as aspect (positive or negative, big or not big, etc.) For example: 行きました. 行 is the Kanji ‘to go’ and きました is the Okurigana showing us that the verb is past tense. Translated then, it is: (I) went.

Furigana (振り仮名) – reading aids you’ll sometimes find next to Kanji.

It is often used in children’s texts, as well as for difficult Japanese names and for puns and double meaning. Furigana is usually written using Hiragana (and occasionally Katakana). They can be useful for saving time when learning Japanese (to avoid having to look up the readings of lots of words in the dictionary), but can also be dangerous if you come to rely on them. Use sparingly.

Leave a Reply