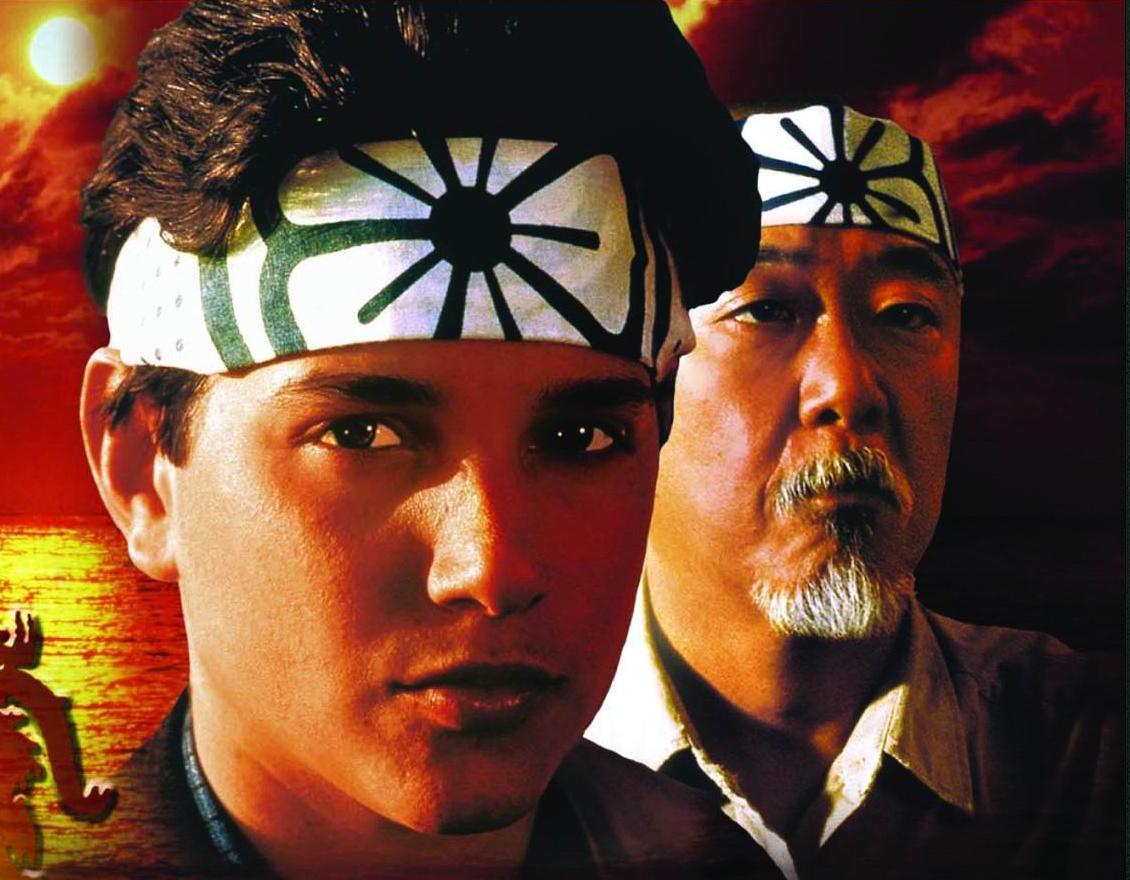

‘Honorific’ is a linguistic term referring to titles added to a person’s name. In Japanese, the vast majority of these are suffixes. You’ve likely have heard one or two in movies: ‘Daniel-san’ and ‘Miyagi-sensei’ spring to mind. Honorifics aren’t just limited to suffixes however. In English for example, we generally use prefixes added to a person’s name, such as ‘Mr.’, ‘Mrs.’ or ‘Ms.’.

What all of these have in common is that they are used to signify status or imply some sort of respect. Just like in English, most of the time honorifics are added when addressing strangers or people of a higher standing than yourself. There are a few variations in English, such as ‘Dr.’ or ‘Sir’, but the Japanese language has comparatively more of them, and a far more nuanced lineup at that. First though, it’s important to be aware of the tendency not to use names at all!

Social Dynamics

When addressing somebody in Japanese, their title or position takes priority over a personal name. The boss of the company for example, will usually be addressed as Shacho (社長) by his subordinates. Similarly, family roles take priority over names. Okaasan (お母さん) and Otousan (お父さん) – Mum and Dad – for example are universally used by all family members to refer to the parents of the young children in the household (including by Mum and Dad themselves, often even when speaking just to one another).

For people without status, those lower than yourself or strangers (people with whom you have no way of comparing social status), names with the suffix -san are usually used. The boss will address his subordinates with surname-san, or sometimes just by their surname or name alone, to signify the difference in social position. In the family, younger children will be called by their own names, but in return they must usually call their older siblings by Oniisan (お兄さん) and Onesan (お姉さん), meaning older brother and older sister.

Another point to note is that, while there are generalised rules for using honorifics, often a title can be adopted as a nickname. However, this is usually at the request (or at least begrudging acceptance) of the individual whose nickname it is.

It can all get rather confusing and class-based relationships in Japanese society are intricately complex and a topic worthy of its own post. Getting this area of social etiquette wrong can be offensive though, so be sure to check out this complimentary article discussing the issues here!

In this post we’ll continue to examine the different types of honorifics, focussing on titles and name suffixes.

Name Suffixes

さん

-san

This is the universal suffix attached to the name of almost all animate and many inanimate objects.

For example:

田中さん

たなか さん

Mr/Mrs/Ms Tanaka

You’ll notice that we’re unable to tell the sex of the person whom the suffix is attached to – a striking difference to English.

Another example:

パン屋さん

ぱんや さん

The Baker / The Bread Shop

Because there’s no gender involved, adding -san to inanimate objects can also show a degree of respect. There’s some ambiguity here though as to whether or not we’re referring to the shop itself or the person who runs the shop, but the usual emphasis is on the people involved.

What’s important to remember then is that the suffix is there, implying respect and politeness. It’s businesslike – a little cold – and because of that, leaving the suffix off a name implies a strong closeness to the person, which can be extremely rude if no such relationship exists!

For example, old friends who have known one-another since childhood would be one such scenario where leaving -san off the (first)name would be acceptable and preferred. Just like in many western societies, calling somebody by their name creates a friendly atmosphere by demonstrating equality. Both parties are brought down to the same level.

“That’s the name they lick me by. I’m Tom when I’m good. You call me Tom, will you?”

[The Adventures of Tom Sawyer]

If there is no intimate relationship or one of the parties feel that the equal relationship is inappropriate, leaving the suffix off the name will come across as rude. As a general rule, the -san suffix should always be used when addressing strangers, in business situations or when unsure about the level of formality required. It usually becomes apparent when appropriate to drop -san by the atmosphere around you and by listening to how others are speaking to you. But don’t tread too lightly – just because somebody drops the suffix when addressing you, does not mean you should do so in return!

様

-sama

The ultra-formal equivalent of -san and a term of both great respect and humility, simultaneously raising the listener up and pushing the speaker down. This suffix is used when addressing people in very high social positions and expresses strong deference by the speaker. Knowing when to use it all depends on your own social position!

The most common usage you’ll run across in day-to-day life is when out shopping. The plethora of businesses and shops around you all want your money. Because of this, they show deference. You are the お客様 (okyaku-sama) – the esteemed customer.

In business situations, especially in written and electronic communication, -sama is often used as the default honorific when addressing people outside of the immediate organisation (or those very high up in the same organisation). When writing an email, for example, the format is pretty fixed. Begin with the company name, followed by the person’s position, followed by their surname-sama.

株式会社ソニー

デジタルイメージング事業本部

田中様

かぶしきかいしゃ ソニー

デジタルイメージング じぎょうほんぶ

たなか さま

Sony Corporation

Digital Imaging Business Group

Mr. Tanaka

When there is no obvious gap in social status however, using -sama can come across as grovelling. Think of the humble servant Igor…

Yes, Master…

Because of the politeness and deference this word conjures up, the term can also be used for comedic effect, being deliberately employed in situations that clearly do not warrant usage of the word. The ultra-masculine way of referring to oneself is often used in manga to depict ‘bad-boy’ types and villains: 俺様 (ore-sama) – my magnificent self.

俺様の言うとおりにすればいいんだ!

おれさまの いうとおりに すればいいんだ!

All you need do is exactly as I tell you!

It’s also interesting to note that the term 貴様 (kisama) – honoured sir – was originally used to show great respect to important authority figures, but whose usage has since been twisted. It now roughly means something like ‘you bastard’ (or worse).

ちゃん

-chan

After -san and -sama, suffixes become much more flexible. The suffix -chan for example revolves around cuteness. It’s a term of endearment usually used towards girls, pets or young children in the form of a nickname. It’s often translated as ‘little’ (little things generally being seen as cute).

That said, it has quite a broad usage and you’ll hear it used affectionately between friends, lovers, couples and in reference to mascots and other objects that fall under the broad banner of ‘cute’. This includes guys who have a demonstrably cute quality to their personality! In English we might achieve this effect by transforming somebody’s name into a cuter nickname. ‘Michael’ might become ‘Mikie’, for example.

アマちゃん

アマちゃん

Little Diver / Diving Girl

As with other suffixes however, mistaken usage can sometimes be rude, so exercise caution. Generally though, you won’t be using this term around formal environments, and in informal settings it can be fun to use in breaking the ice.

There are also several corruptions of -chan in use, the most prevailing of which is -tan, used for mascots in advertisement and also for anime. Probably the most well-known are the OS-tan – mascots for each computer operating system.

君

-kun

A little similar to -chan, but used in reference to boys and other males. Like -chan, this suffix shows endearment towards the person being addressed but is more mature and a little less intimate. Because of this, -kun can be used in more formal environments such as the office, particularly between male peers in reference to someone of lower social standing, as well as towards young boys who seem to not quite fit the ‘cute’ profile implied by the -chan suffix.

たろう君

たろう くん

Taro

先輩

-sempai

Senpai is an honorific usually used as a regular word to show the difference in social status between the speaker and listener. It translates loosely to ‘mentor’ or ‘senior’ and as such you’ll most often find it in school environments and clubs where progress is graded and monitored. It’s also used in the workplace and other fields however in reference to somebody who is more experienced or who joined the organisation before you. As a suffix, it’s attached to the end of a person’s name just like any other.

The opposite of sempai is ‘kouhai’, meaning ‘junior’. It is used as a regular word, although not often directly to the person as it would be rude. It’s also the reason you don’t hear it used as a suffix.

先生

-sensei

Literally ‘came before’, referring to a teacher or master of a subject. In English we think almost exclusively of martial arts teachers when we hear this term (thanks in no small part to the influence of popular 80’s film ‘The Karate Kid’), but the term is used in Japan in a much broader sense. It is the standard for doctors, dentists, teachers (all varieties), scientists (although for those with a doctorate the term 博士 – hakase – is usually used), writers, lawyers and pretty much anybody else you can think of that would be best described as a ‘master’ of a craft.

It’s interesting to note that the term can also be applied scathingly towards people who aspire to be seen as a master but have not been acknowledged by an outside authority, or in jest to acknowledge the speaker’s deference to the listener’s authority on a subject.

氏

-shi

Similar to -sensei, this term is used in formal writing and speech to refer to someone unfamiliar to the speaker. As such, it has frequent use in academia, formal publications, journals, legal documents and newsreaders. It is sometimes also used in jest in business environments in the same way that -sensei is, to show recognition of somebody’s knowledge on a topic.

**********

It’s been a long post! As a final note, using no honorific at all when addressing someone is known as 呼び捨て (yobisute) – literally ‘throwing away the calling’. This is considered quite rude, although for most foreigners in Japan it will occur unwittingly at some point. Most listeners will not wish to point it out and cause embarrassment, but it rarely goes unnoticed. Special care should be made to avoid addressing somebody in this way! Best of luck!

Leave a Reply